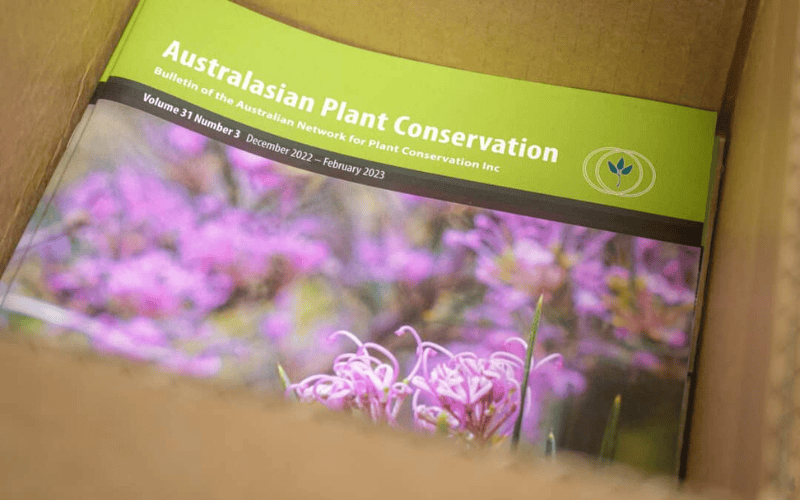

Australasian Plant Conservation

About the bulletin

Australasian Plant Conservation (APC) – the quarterly bulletin of the Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC) – is a forum for information exchange for all those involved in plant conservation, whether in research, management, or on-ground practice, and where they can share their work with others. Each issue contains a range of articles on plant conservation issues, usually on a particular theme, which reflect the interests of the range of ANPC’s membership. However, off-theme articles are welcome at any time. Regular features include lists of the latest relevant publications, membership profiles, Australian Seed Bank Partnership news, and conference and workshop reports. APC publishes articles from the breath of fields that inform plant conservation in Australasia, including, but not limited to, ecology, botany, conservation biology, aquatic botany, bryology, mycology, restoration, horticulture, social science (e.g., community environmental management), natural resource management and environmental policy. The role of APC is to provide a common forum accessible to scientific researchers, land and natural resource managers and ecological consultants, and community practitioners. APC is a great way for scientists to communicate their findings to practitioners, and conversely for practitioners to report their work and practical issues in a scientific forum; an important part of APC’s role is to provide an avenue for practitioners with limited or no scope for publication in their field. Student and trainee papers are encouraged, as are papers from our Australasian neighbours (e.g., New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia). To the extent possible, and except for policy articles, we prefer material which includes at least indicative results and some attempt to identify generalisable results (not simply ‘we did this’, but ‘here’s what it means in our situation’). APC is published quarterly and is provided free to ANPC members within Australia and worldwide as part of their subscription. An index of past APC issues can be found here.

Article review

Australasian Plant Conservation is not a ‘peer-reviewed’ journal, but it is edited to a high scientific and technical standard, in liaison with authors as necessary. We seek to operate at the interface of the science and management of plant conservation, publishing information which can be applied to improve plant conservation.

Upcoming APC issues

| Issue | Date | Theme(s) | Call for papers | Deadline for articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33(4) | March – May 2025 | APCC14 Conference issue | December 2024 | Closed |

| 34(1) | June – August 2025 | APCC14 Conference issue | March 2025 | 1 May 2025 |

| 34(2) | September – November 2025 | General | June 2025 | 1 August 2025 |

| 34(3) | December 2025 – February 2026 | General | September 2025 | 1 November 2025 |

Author guidelines

Please read through the information below to ensure your submission meets the required guidelines. Please include all required files in your submission to the Editor. Submissions with missing files or incorrect formatting may result in a delayed publication.

Article presentation

Authors are asked to keep our broad readership in mind – we seek articles that are as far as possible ‘plain-English’, without being dumbed down. Please take space in your draft to briefly explain (rather than assume) technical terms or concepts, or local situations, that may be unfamiliar to other sections of the readership. Please discuss with the editor if in doubt.

Article categories

Australasian Plant Conservation publishes the following article types. All submissions go through the same editing workflow as mentioned above.

Articles

The main submission for the bulletin and are complete reports on a topic in plant conservation. The text structure of these is broad but the use of sub-headings, figures and images is strongly encouraged. They are typically up to 1200 words (the word limit refers to the main text body and headings and does not include references or figure and table captions).

Short Communications

Smaller submissions and are best suited concise disseminations of information that do not fit a complete report style as per the Article type but provide important updates, insights or outcomes relevant to plant conservation. These generally should not exceed 500 words in length (not including references) and be accompanied by one or two key figures, images, or tables.

Translocation Case Study

Plant translocations are important intervention actions in plant conservation, but their motivation, outcomes and learnings are oftentimes not communicated for various reasons. To support the communication and publication of plant translocations, APC has a specific translocation case study template with required headings here. Please use this proforma for submitting translocation articles. These should still follow the correct text and reference formatting and figure presentation that are outlined below.

Correspondences

Similar to Short Communications but their purpose is for providing a forum for short comments on topical issues, anecdotal material and reactions to material published in APC. They should be no longer than 300 words and three or fewer references. We suggest that authors try to make one or two clear points and include relevant context to ensure their correspondence is ‘durable’ (time to publication may be up to 3 months). Tables and figures are not usually included in correspondence. Please note: selection of Correspondence for publication in APC will be based first on relevance and interest to the readership of APC, and according to the principles of balance and fairness where necessary (e.g. right of reply). While authors are encouraged to express their opinion, the Editor will check for factual errors. Furthermore, publication of correspondence will be at the discretion of the Editor, in consultation with the President of ANPC (where necessary) and will be reviewed by members of the ANPC committee. Correspondence may be edited for publication (the author will be advised).

Photos from…

A new inclusion in APC from 2023 encouraging submissions of images that highlight current work in plant conservation. Each submission requires a single high-resolution image and accompanying extended description providing context to the image and identifying its importance and relevance to plant conservation. Examples include an image of a rare plant species found in the field, a recruitment event post-fire, a new technology in the laboratory, nursery or field, or a recent inclusion in a living collection. The written component should be at least 100 words and not exceed 300 words. References are not required for this submission.

Other submission types

We also welcome submissions for book reviews, titles of interesting recent publications or resources, and where they can be found, conference, workshop, course and fieldwork announcements, and details of relevant publications, information resources and websites. Such submissions are incorporated into regular features of APC (e.g., ‘Research Round up’).

Article submission

| The deadlines for submitting articles to APC bulletins are available in the table above. Specific article enquiries including initial discussions on article ideas prior to submission should be addressed to the Editor. Authors are encouraged to read recent issues of APC to become familiar with the scope, details and format of articles. All submissions must be accompanied by an Article Submission Form available as a PDF or DOC file. Please email your submission to the Editor prior to a bulletin deadline via the email: editor@anpc.asn.au |

Title page

This should include the following information:

- Concise title for the article

- Names and affiliations (organisations) of all contributing authors

- Email address and phone number of the corresponding author

Text

Submissions must made using an electronic filetype such as Microsoft Word (.doc or .docx) or Rich Text Format such as WordPad (.rtf). Further information regarding APC styling can be viewed by downloading the Article Template

All submissions should be in a style readily accessible to the diverse readership. Ensure all technical terminology is explained at their first usage.

Headings and sub-headings: the text should be divided into sections with headings and sub-headings for Article submissions. Headings and sub-headings can also be used for Short Communication and Correspondence where required. Please only use a capital letter for the first word and proper nouns.

Spelling and formatting: use Australian English, for example, ‘colour’ not ‘color’, and use ‘s’ not ‘z’ in words such as ‘organisation’, ‘recognise’ etc. (unless, for example, in titles of already published documents in reference list).

When referring to the species by its common name, please provide its scientific name in brackets (after the common name) the first time the species is mentioned. Common names should be capitalised, as in: Red Box, Grand Spider-orchid, Rainbow Plant. When referring to the species by its scientific name only, it is at the authors’ discretion whether the common name is given, or not. Currently accepted scientific name should be used as agreed by the Council of Heads of Australasian 8 Herbaria (CHAH) in the Australian Plant Census (http://www.anbg.gov.au/chah/apc/). APCensus usage is preferred, unless there is a case for variant usage to suit a State-specific or international context – in this case please make the nomenclatural equivalences explicit. Use ‘subsp.’ rather than ‘ssp.’ for subspecies.

Formal species listing status should be capitalised (e.g., Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable) and relevant jurisdiction or government act (e.g., IUCN Red List, NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act) given at first mention.

Spell out all numbers less than 10. For example, “three” rather than “3”, unless it is followed by a unit, for example, 3 km. When reporting numbers 1,000 and up, please use a thousand separator (i.e., place a comma between each group of three digits). Place a space between number and unit (i.e., 3 km), use en-dashes to separate numbers (e.g., 10–15 cm), and year ranges should be written in full (e.g., ‘1995–1996’ rather than ‘1995–96’). There should be no spaces beside symbols +, – and ~ when they are followed by a number. There should also be no spaces beside forward and back slashes (e.g., and/or), or between a number and a per cent symbol (e.g., 20%) or between a number and degree symbol (e.g., 15°C).

No full stop is required after abbreviated titles (i.e., use ‘Dr’ rather than ‘Dr.’). Seasons should not be capitalised (e.g., summer, autumn). North, east, south and west should not be capitalised when they are used to indicate a direction or general location; however, they should be capitalised when they form part of a specific region or proper noun. Similarly, words such as ‘national park’ and ‘state forest’ should be capitalised when referring to specific national parks or state forests, and not when writing about national parks and state forests in general. Abbreviations: spell out abbreviations when first used followed by the abbreviation in parentheses, for example, “Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC)”. Do not use full stops in abbreviations comprising capital letters, for example, “ACT”. Italicise Latin abbreviations (use italic font), for example, “et al.”, “ex situ”, “in situ”.

Paragraphs and lists: separate paragraphs by a blank line and do not indent the start of a paragraph. Use single ‘quotes’ in text. Information lists are a useful method to present key points or information. In these instances, use bulleted entries.

Images, figures and tables

All images, graphs, charts or other illustrative figures must be submitted to the Editor as separate files. Images embedded into the text file will not be accepted. Tables can be created and embedded into the text file using Microsoft Word or similar program. Please include in the text submission file an approximate indication of where each image, figure or table should be placed. Each figure and table must be referred to in the text. Each image, figure and table file should be named separately and logically, including the manuscript author’s name and figure number (e.g. “Smith_Fig1.tif”) Photographs should be 300 dpi resolution and be submitted with at least 1500px on the longest size for publication. Accepted filetypes are: .tif, .jpg, .png or .gif. Each image should be submitted separately even if they form a collage or multi-panel figure. In these instances, the images may need to be re-arranged to meet formatting restrictions and design requirements. Do not use add letters, for example, ‘a’, ‘b’ and ‘c’ into an image if it is part of a multi-panel figure, but include the letter in the file name instead. Graphs or line drawings can be submitted similarly to photographs; however if Microsoft Excel was used to create graphs then please supply the original excel file separately, naming the file as per above. The following symbols should be avoided: ‘+’, “x” or “*” as they do not reproduce well. Any symbol should be explained in a figure legend or caption. Any lettering should use a sans-serif font such as Arial or Calibri. Tables should include horizontal lines only (no vertical lines). Each table should have a brief title or caption that should make sense without the need to read the text.

References

In the text, references should be in chronological order. Multiple references should be separated by semi colons. Use “and” where there are two co-authors and “et al.” where there are more than two co-authors. Do not use a comma between author name and year. Government Acts should be italicised (e.g., Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). Referencing should be kept to a minimum and restricted to key references. All items in the reference list should be readily available. Where necessary, further detail can be given on methods of access (in brackets after the record). Please pay particular attention to formatting of author list (i.e., abbreviation of first names, spacing within abbreviations), presentation of year (in brackets, followed by full stop), italicisation of some fields (varying with reference type) and the use of “and” rather than “&”. Incorrectly formatted references will be returned to the author for re-formatting. If websites or email addresses are cited in the main body of the text they should be bold formatted.

*Please note: the referencing of articles differs to that within the APC section “Research Round up”.

Journal article: Constanza, R., D’Arge, R., De Groots, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neil, R.V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R.G., Sutton, P. and Van Den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253-260.

Online journal article: Kriticos, D. J., Morin, L., Leriche, A., Anderson, R.C., and Caley, P. (2013). Combining a climatic niche model of an invasive fungus with its host species distributions to identify risks to natural assets: Puccinia psidii Sensu Lato in Australia. PLoS ONE 8(5): e64479. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0064479

Book: Briggs, J.D., and Leigh, J. H. (1996). Rare or threatened Australian plants. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne. Section or chapter within a book: Erickson, T.E. and Merritt, D. J. (2016). Seed collection, cleaning and storage procedures. In: Erickson, T.E., Barrett, R.L., Merritt, D.L. and Dixon, K.W. (Eds.) Pilbara seed atlas and field guide: plant restoration in Australia’s arid northwest. pp. 7-116. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Report (available online): Hancock, N., Harris, R., Broadhurst, L. and Hughes, L. (2016). Climate-ready revegetation. A guide for natural resource managers. Macquarie University, Sydney. Available at: https://anpc.asn.au/resources/climate_ready_revegetation 12

Report (not available online): Sattler, P. and Williams, R. (1999). The conservation status of Queensland’s bioregional ecosystems. Environmental Protection Agency, Queensland Government, Brisbane.

Thesis: Hall, K.B. (2015). Modeling the actual productivity of Eucalyptus benthamii in the Southeastern United States. Thesis for degree of Master of Science, Forestry and Environmental Resources, Raleigh, North Carolina. · Website Australian Government (2016). ‘EPBC Act List of Threatened Flora’ (Australian Government Department of the Environment: Canberra). Available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgibin/sprat/publicthreatenedlist.pl?wanted-flora

Acknowledgements and conflicts of interest

Sources of funding should be declared within the acknowledgements section. Contributions of colleagues who are not listed as an author should be acknowledged. Please ensure the permission for everyone acknowledged has been granted. A conflicts of interest section can also be included after the acknowledgements section, identifying any financial, political, personal or professional relationships that may be understood to have influenced the manuscript.

Advertise in APCPromote your organisation or business to ANPC members. Full colour advertising is available throughout APC! Please see our advertising rates here. All fees received help contribute towards the costs of printing and distributing APC. Subscribe to APCAustralasian Plant Conservation is sent to ANPC members four times a year. When you have become a member, you will receive the previous two issues of APC for the calendar year you join. APC IndexSee the list of APC bulletins here from the present back to 1995, with a limited number of articles available to display. You can download a copy of all articles from APC Volume 13 Issue 1 to the present from Informit at a cost of $4.00 per article. |

APC Editor – Alyssa Weinstein

Allyssa Weinstein with Button wrinklewort flowers

Alyssa has great enthusiasm for plants, science communication, and bringing science, government, industry, and community together to effectively conserve biodiversity. These interests have led her to roles with United Nations Environment Programme, the Australian federal government, as well as in academia. Alyssa is currently working as a consultant for UNEP, bringing her experience to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem services. She previously worked at the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment, and Water, ensuring effective environmental regulation under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, as well as working in the international policy space. Alyssa’s love for plants flourished growing up in the southwestern Australian biodiversity hotspot, where she completed her Honours at Kings Park and Botanic Garden, before moving to Canberra to pursue a PhD at ANU. In her thesis she investigated the pollination ecology of sexually-deceptive orchids, focussing on the genera Cryptosylis and Drakaea. Fortuitously, her work with Drakaea led Alyssa to a role assisting in the production of the hammer orchid sequence in David Attenborough’s Green Planet, a true highlight of her experiences as a science communicator.

Featured articles

How and why community-based environmental groups are integral to recovering and protecting threatened plant species. Australasian Plant Conservation 33(4): 14-16. For decades, environmental groups have been integral to recovering threatened plants. This paper explores this role, using this analysis to describe some of the key activities of the Queensland Threatened Plant Network (QTPN). The QTPN is a collaborative project established by the Queensland Government and the Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC) that provides support to stakeholders contributing to threatened plant recovery in Queensland. The Network actively facilitates the formation of partnerships amongst interested parties working to conserve Queensland’s threatened flora. QTPN seeks to elevate the vital role that these groups play in the protection and conservation of some of the rarest flora in Queensland. [Full text PDF].

For decades, environmental groups have been integral to recovering threatened plants. This paper explores this role, using this analysis to describe some of the key activities of the Queensland Threatened Plant Network (QTPN). The QTPN is a collaborative project established by the Queensland Government and the Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC) that provides support to stakeholders contributing to threatened plant recovery in Queensland. The Network actively facilitates the formation of partnerships amongst interested parties working to conserve Queensland’s threatened flora. QTPN seeks to elevate the vital role that these groups play in the protection and conservation of some of the rarest flora in Queensland. [Full text PDF].

Science Saving Rainforests: restoring genetic diversity to 60 tree species of the critically endangered Big Scrub rainforest. Australasian Plant Conservation 33(3): 3-5. The Science Saving Rainforests (SSR) Program is a large landscape-scale multi-species restoration project that aims to address the lack of genetic diversity in the remaining patches of Critically Endangered Lowland Rainforest of Subtropical Australia (LRSA) (EPBC Act 1999), with a particular focus on the small isolated remnants of the Big Scrub Rainforest in North-eastern New South Wales (NNSW). Long term outcomes from the SSR Program will include the production of genetically diverse planting stock for 60 LSRA tree species for use in restoration projects that will increase adaptive potential and resilience to future threats such as predicted climate change conditions, new pests and emerging diseases. [Full text PDF].

The Science Saving Rainforests (SSR) Program is a large landscape-scale multi-species restoration project that aims to address the lack of genetic diversity in the remaining patches of Critically Endangered Lowland Rainforest of Subtropical Australia (LRSA) (EPBC Act 1999), with a particular focus on the small isolated remnants of the Big Scrub Rainforest in North-eastern New South Wales (NNSW). Long term outcomes from the SSR Program will include the production of genetically diverse planting stock for 60 LSRA tree species for use in restoration projects that will increase adaptive potential and resilience to future threats such as predicted climate change conditions, new pests and emerging diseases. [Full text PDF].

Creating an optimised population of Sydney’s newest Eucalypt. Australasian Plant Conservation 32(4): 14-16.

After decades of puzzling taxonomists, genetics was used to support morphological studies and confirm a new species of Eucalypt. The new species received the name Eucalyptus cryptica. Eucalyptus cryptica is critically endangered and occurs only in northern Sydney in a cluster of fragmented populations, on private land at risk of development. The populations are threatened by genetic isolation and hybridisation, as well as weeds and changing fire regimes. To conserve the populations, geneticists identified least related plants and designed a new population which maximised genetic diversity. [Full text PDF].

Why Australia needs an Ecosystem Restoration Strategy. Australasian Plant Conservation 30(4): 13-18.

Australia needs a national strategy for ecosystem restoration. 2021 marks the beginning of the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restorationwhich aims to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems globall

y. In Australia, land use practices and invasive species are two of the most pervasive threats that have caused land degradation. We owe it to future generations of Australians to halt and repair as much of this environmental damage as we can, especially given the new and acute stresses that climate change is now imposing. [Full text PDF].

Recent book reviews

Allure of Fungi by Alison Pouliot. Review by Michele Kohout. [PDF] Australian Forest Woods by Morris Lake. Review by Jugo Ilic. [PDF] A Guide to Native Bees of Australia by Terry Houston. Review by Paul Kucera. [PDF] Restoring Farm Woodlands for Wildlife by David Lindemayer et al. Review by David Cheal. [PDF]